Down 39 kilometers

On October 14, 2012, Austrian extreme athlete Felix Baumgartner jumped out of a capsule that had previously travelled to an altitude of almost 39 kilometers by means of a helium balloon. In a free-fall from the stratosphere back to Earth, he reached a speed of 1357.6 km/hour and was the first human being to break the sound barrier without the use of an aircraft. He opened his parachute 1585 meters above ground and landed safe and intact.

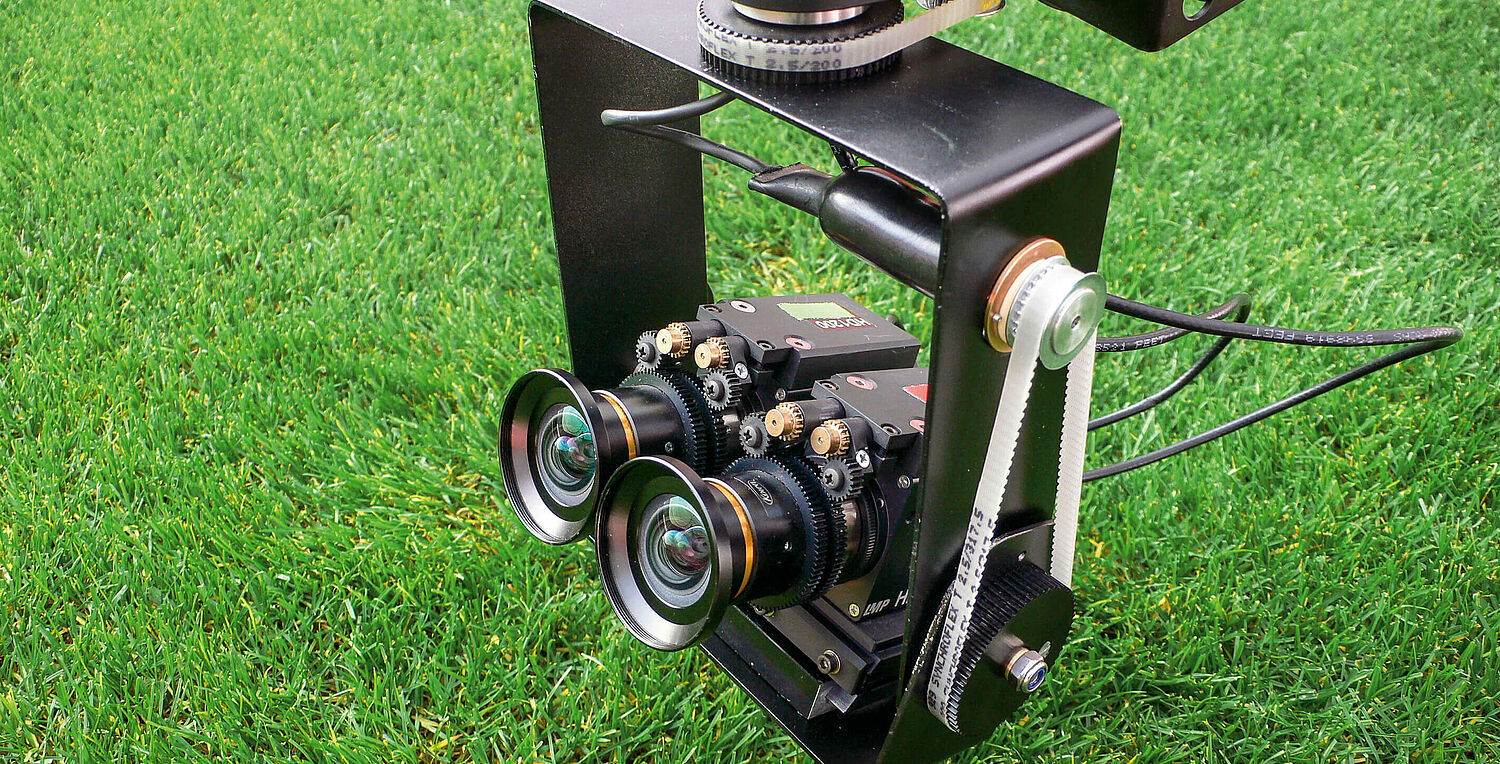

TV stations around the world televised the preparations and the jump. The broadcaster of the main sponsor reported on the event live over more than 10 hours. Nine cameras delivered spectacular images – five inside the capsule, two showed the exterior of the capsule, and two more were attached to the performer’s body. The shutters and sharpness of the cameras were adjusted from the ground via remote control.

“The biggest challenge for the devices was heat,” explains Friedel Lux, pointing out an unexpected obstacle, considering the freezing temperatures in the stratosphere. “The unfiltered sun radiation heated the housing enormously. And at that altitude there is no air to carry away the increasing heat. So the cameras had to withstand quite a lot.”

Industrial camera on ski jump tower

Originally, the founder and technical director of LMP developed it for “regular” professional sports. With his unique equipment designs for recording and image transmission, he had previously made a name for himself as a service provider for TV productions. In 2002 for the Olympic Winter Games, he received an inquiry from an Italian TV station on whether it would be possible to mount an HDTV camera at the starting position of the ski jumpers at the top of the ski jump tower. “The space is very tight there, and the recorder wasn’t to get in way, of course,” he recounts. “So we took a still rarely used camcorder and dismantled everything that wasn’t critical to video recording.”

The tiny device that remained enabled the TV station to literally look over the jumpers’ shoulders. It didn’t take long for other types of sports to discover the appeal of up-close footage. In 2004, LMP in cooperation with TV-Skyline for the first time mounted a camera on the net strut of a soccer goal, which showed every movement of the goalkeeper from behind and at the same showed a view of the entire game situation from his perspective. The device could only protrude 3 cm into the area of the net.

The second generation was released in 2008: was completely further developed in-house under the commercial name "Cerberus" and it is still used today. You can find it in handball goals as well as on crossbars for pole vaulting and many other places where fans want a close-up view. The camera head of the Cerberus is no bigger than three regular-size matchboxes stacked on top of each other.

Hellishly efficient drive for Cerberus

An even smaller version was developed for installation into the pole of a corner flag on the soccer pitch. It is currently being used in two top games of every match day in the Bundesliga. The cameras mounted on mobile cranes, which are part of everyday life in team sports in the top leagues, are also from LMP in many cases. “In this case, it’s more about the weight than the size,” explains Friedel Lux. “The lighter the camera, the faster and more precisely the crane can perform the desired movements.”

The drive unit mounted on the camera plays a decisive role in the function of the Cerberus. It performs the mechanical work of adjusting the shutter and focus via a gear train. To do this, LMP uses DC-motors from the 0816 … S series and 08/1 gears with a diameter of eight millimeters from FAULHABER. The diameter of the corner flag camera is slightly larger, but the motors are shorter.

“For these types of applications, we need as much torque as possible with the smallest possible mass and volume,” the camera specialist points out. “The gearhead is almost more important. It has to withstand a lot and must be very robust. At the same time, it must ensure that the drive unit functions very precisely. Our top priority is that there are no sudden movements and everything works very smoothly, no fluttering, snagging, or start-up delays. Only then can you actually see whether the goalie is tense and by how many hair's breadths the high jumper cleared the bar.“

But the drive units from LMP are not only used for sporting events. Lens controls for aerospace applications, from Space-X to Boeing and Airbus, are also part of the program. Precision and robustness are also of utmost priority here.

Products